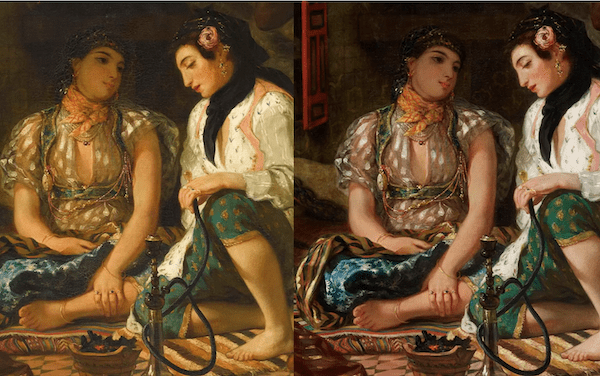

The Women of Algiers in their apartment (Les Femmes d’Alger dans leur appartement), a sublimely beautiful painting by Eugène Delacroix (1898-1863), has just been restored and has regained its colors. A painting that Renoir considered as “the most beautiful painting in the world“, while Cézanne when he speaks about it writes: “these pale roses and these embroidered cushions, this babouche, all this limpidity […] enter you in the eye like a glass of wine in the gullet, and one is immediately drunk“. Charles Baudelaire, of whom we know the acuity and the accuracy of his criticism, pictorial or musical in fact (let us remember his criticism of Tannhauser), compares it to “a small interior poem“. As for Matisse in the following century, he seized with an admiring jubilation the subject and even went so far as to take up in a new temporality the constituent elements of the decor that makes a setting. Picasso will follow…

After a few months of restoration, the painting is once again accessible to the public and presented in the Mollien Room at the Louvre. It thus joins The Massacres of Scio, itself restored in 2019.

Huile sur toile, 180cm/ 229cm. Le Louvre. Paris

Delacroix is one of those rare artists whose creative genius could be expressed in different forms. Thus, he was at the same time this “Phare” (“lighthouse“, an allusion to the famous poem by Ch. Baudelaire) who made the color vibrate to make alive and passionate, almost musical, all the scenes he painted, as well as he was also and at the same time this letter writer who liked to write, his Journal and his Correspondence attest. Victor Hugo was also one of these men, a protean artist, and his drawings and other paintings resonate with his literary and romantic work.

Delacroix discovers Morocco

He writes to his friend Jean-Baptiste Pierret: “Imagine my friend what it is to see lying in the sun, walking in the streets, mending slippers, consular characters, Cato, Brutus, who do not even lack the disdainful air that the masters of the world must have had”.

Paris, Musée du Louvre.

So in January 1832, Eugène Delacroix, then 34 years old, accompanied a French diplomat on an embassy to Morocco, the Count of Mornay (Charles Henri Edgard, comte de Mornay-Montchevreuil ). For the artist, this trip was above all a revelation, a shock, both cultural and aesthetic. Indeed, not only does he discover the light, the sun, but more than anything else he discovers the Arabs living their traditions, dressed in djellabas, and living with serenity the present moment. He is impressed by their dignity, their nobility. The painter until then heir of the neo-classicism of Jacques-Louis David or Pierre-Narcisse Guerin, is upset.

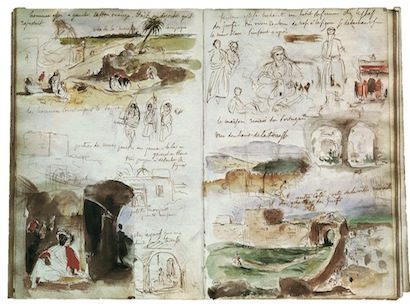

Hence suddenly Delacroix seizes the moment, he discovers under the Moroccan sun the living expression of an antiquity, until then essentially celebrated by the statuary art. To the figures as if frozen in neo-classicism, he finds movement, he resurrects the life that was missing until then, a reincarnation in a word. His numerous notebooks from his trip to Morocco (Cabinet des Dessins du Louvre), his watercolors and drawings give an account of his dazzling painting, and the notes that accompany them provide information. On his return to France he set to work and in 1834 the painting Women of Algiers in their Apartment was presented at the Salon.

Delacroix was also a “drawing fool“, like Hokusaï 葛飾北斎 at about the same period in Japan. He accumulates in his notebooks, which will follow him all his life, a multitude of sketches of everything and nothing, memory aids in a way, a repertoire of forms. For example, the little slipper, the “babouche” seen at the bottom of Women of Algiers in their apartment, is sketched in one of his notebooks, and had already been used for The Death of Sardanapalus.

On the interpretation of facts

Sometimes, historical memory wavers, and the interpretation of facts may not conform to reality. A poorly calibrated choice of documentary sources can lead to false considerations, and the process of inutrition that follows reflects in time what is not and never was. Moreover, historical interpretation against the grain, uchrony, is a pitfall that every researcher should beware of.

Academic reflection, the very essence of the researcher’s analytical work, must be based on the corpus, notably written, the archives in a way. It is this process that defines the intellectual, to which of course doubt must be added. It is to this standard of vigilance that Maurice Sérullaz, the greatest Delacroix specialist, Chief curator of the Cabinet des Dessins at the Louvre, trained his students ( the present writer of this article was one of them). The work of the art historian uses the same methodological tools as those used by historians of the political field of countries and societies.

Delacroix. Carnet de voyage. 1832. Metropolitan Museum; New York

So when it comes to Delacroix, what a boon! Thus one can follow him almost to the trace and this thanks to the reading of his Correspondence, or of his Journal. In Morocco, in Spain, in Algiers. Yet never does he write that he was able to enter or be invited into a Muslim house, let alone a harem in the barbarian city where he stayed only two days! Not a single line, never. The presence of a European on the lands of the Dey was, let us emphasize, rare and unusual at that time. In this respect, the presence of a dhimmi, whether Jewish or Christian, was quite simply impossible in the intimacy of an Arab house. Yet some names of Ottoman women who would have served as models for the painting of the painter are advanced! This assumption (which curiously will be taken again) is the fact of a French critic Philippe Burty (1830-1890) who in fact had no grooves of it !

Of course, and it is not useful to specify it, The Women of Algiers, as we had already evoked it, is a work of workshop. It is not in the least an ethnographic document. It is above all an almost polyphonic painting, a nostalgic, warm and sensual melody in an oriental interior. The central medallion in the background indicates the Qur’anic formula جوهرة الروح which suggests an Arab interior, a way of orienting the viewer’s vision.

If he did not succeed in being received despite his efforts to lose himself in the crowd and enter the intimacy of Moroccan homes, Delacroix on the other hand was welcomed upon his arrival in Morocco by Jewish families.

His interpreter, his drogman, who served as his guide, Abraham Benchimol, was a Jewish merchant from Tangier. Benchimol invited Delacroix to his own home and the two men struck up a friendship. Moreover, Delacroix will be sensitive to the beauty of the wife and daughter of his host: “His wife, his daughter, and in general all the Jewish women are the most piquant women in the world and of a charming beauty. His daughter, I believe, or his sister’s, had very singular eyes of a yellow surrounded by a bluish circle and the rim of the eyelids dyed black. Nothing more piquant. Their costume is charming” he wrote. Delacroix’s travel diaries to Morocco, with sketches of Jewish women, illustrate this emotion felt by the painter. In 1841 Delacroix will present The Jewish Wedding.

Restoration of The Women of Algiers in their apartment

Here is what the restoration services of the Louvre Museum wrote: The pictorial layer of the painting has remained in good condition, without wear and tear and with very few retouches over time. But its visual appreciation had been deteriorating for several decades, due to the many layers of oxidized varnish that covered it. This thick screen caused a yellowing, darkening and optical flattening of the composition: the whites, although very varied, were reduced to the same ochre shade, the opacity of the varnishes reduced the illusion of depth of space, while one could hardly distinguish the objects evoked in the background (the corner piece of furniture, the fabrics rolled into a ball, the variations of the wall tiles).

Such impaired visibility gradually reduced the work to its subject alone; one lost sight of the colorist virtuosity that had made Femmes d’Alger a model for the generation of Impressionist and Neo-Impressionist painters. Fantin-Latour copied it, Renoir imitated it, Paul Signac set it up as a lesson in the “application of the scientific method” of simultaneous color contrast.

After being the subject of a scientific imaging campaign to better understand its material history, the work passed through the expert hands of Bénédicte Trémolières (for the paint layer) and Luc Hurter (for the canvas support) in the workshop of the Centre de recherche et de restauration des musées de France (C2RMF).

The restoration of an icone of modern painting

Most of the deteriorated varnish has been removed; the appearance of certain cracks in the material has been reduced. A new natural varnish has completed the restoration of the saturation and contrast of the colors. The work can now be appreciated by understanding these lines of the painter Paul Signac: “In the Women of Algiers, […] all the warm and cheerful colors will balance with their cold and tender complements in a decorative symphony, from which the impression of a calm and delicious harem emerges wonderfully” (D’Eugène Delacroix au néo-impressionnisme, Paris, 1899).

The campaign will continue in the first half of 2022 with a study prior to the restoration of another Delacroix masterpiece, The Death of Sardanapalus – a restoration that will be carried out thanks to the patronage of Mme Isabelle Ealet.The Scenes from the Massacres of Scio and The Women of Algiers in their Apartment can be discovered or rediscovered side by side in Room 700, on the second floor of the Denon wing at Louvre Museum in Paris.