In his latest book, La fin des illusions, Politique, économiques et culture dans la modernité tardive, German sociologist Andréas Reckwitz takes as his starting point the observation that the expectations many people in Western countries had of social change since the end of the Cold War in 1989-1990 have been disappointed in their very foundations. Until a few years ago, social progress was taken for granted in Western public opinion. The global triumph of democracy and the market economy seemed inescapable; everywhere, liberalization and emancipation, the knowledge society and diverse lifestyles seemed to be the order of the day. But recent events such as Brexit or the election of Donald Trump have painfully shown us that this was just an illusion.

It’s only now that we can clearly see the extent of the structural shift from industrial modernity to the singularity society of late modernity. Industrial modernity has been replaced by a late modernity marked by new polarizations and paradoxes, where progress and malaise go hand in hand. The author analyses in detail the contradictory structures of contemporary society, which resist both simplistic narratives of progress and alarmist diagnoses of decline, and underlines the difficulty of tolerating this ambiguity.

The starting point of Andréas Reckwitz’s perspective on contemporary society is that we have been witnessing a profound structural transformation of society over the past thirty years, involving the transition from classical modernity, or industrial modernity in which the rules of the general and the collective reigned, to a new form of modernity: late modernity. This structural transformation began in the 1970s-1980s with the arrival of a number of emblematic events: the 1968 student revolt, the oil crisis and the collapse of the centralized Bretton Woods global financial system in 1973, but also the appearance in 1976 of the first affordable personal computer, the Apple 1.

Late modernity reached its peak in the 1990s. It is characterized, among other things, by radical globalization, during which the sharp division between “first”, “second” and “third world”, typical of industrial modernity, abolishes itself and the North/South boundary becomes increasingly blurred. Some regions in the South are undergoing rapid modernization, while others in the North are losing their pre-eminent status.

In contrast to the society of equals of industrial modernity, late modernity increasingly takes the form of a society of singularities, oriented towards the manufacture of particularities and singularities, towards the premium on qualitative differences, individuality, particularity and the exceptional.

In five chapters, Andréas Reckwitz analyzes this transformation in culture, politics, economics, labor and education. Drawing on a wide range of social science studies, he develops a novel, lucid theory of modernity that follows on from his earlier work The Society of Singularities, A Structural Transformation of Modernity1 and reveals the main paradigms of the contemporary world: the new class society, the characteristics of a post-industrial economy, the struggle for culture and identity, the exhaustion caused by the imperative of self-realization and the crisis of liberalism.

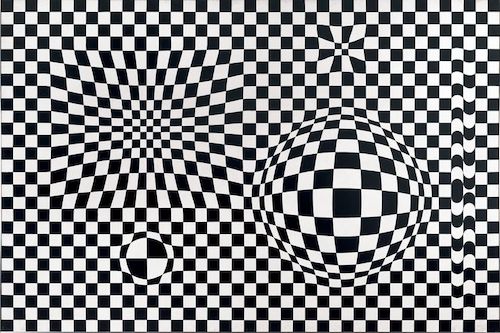

Photo © Centre Pompidou / Philippe Migeat © Adagp, Paris, 2018

In chapter IV of the book, entitled La fatigue de se réaliser soi-même : L’individu de la modernité tardive et les paradoxes de sa culture émotionnelle, the author paints a portrait of late modern man as an overworked, over-solicited subject, presenting pathologies of exhaustion such as depression and burn-out. This “crisis of self” is part of a causal relationship with far-reaching social developments such as capitalism and digitization, as well as a trend towards individual introspection that constantly encourages people to reflect on and transform themselves. Yet this “subjectal culture” produces stubborn paradoxes insofar as late modernity promises subjective fulfillment to the individual and suggests that he or she possesses a right to realize it, while at the same time regularly allowing this accomplished subjective state to appear as a fantasy that real life hardly ever satisfies, except perhaps in certain exceptional moments.

In this context, emotions and affects play a central role. In line with so-called “positive psychology”, late modern culture extols the production of positive emotions as what gives meaning to life and enables access to happiness, without taking into account the fact that it increasingly generates negative emotions while lacking a legitimate place in which to confront these negative emotions. Failure is part and parcel of such a program of self-realization and authenticity, insofar as the late-modern subject finds fulfillment only in the singular, for only that which is singular appears authentic.

The paradoxical situation of this subjectal structure manifests itself in terms of emotions: the positive emotions expected from unlimited self-realization, coupled with recognized social success, are almost systematically met with disappointment linked to the perception of a gap between this expectation and reality, disappointments that are a source of negative emotions. When they persist, these unassimilable negative emotions can lead either to depression or to aggressive behavior.

Faced with such a seemingly limitless dynamic of self-realization, personal fulfillment is thus subject to the pattern of endless growth. Ideally, therefore, we are never content with the way of life we have found, but always seek the challenge of novelty. This is accompanied by an aversion, characteristic of our times, to renunciation, which is seen as something negative, even pathological.

The author looks at a way of life that would enable us to break out of the spiral of disappointment, which is not necessarily problematic in itself. In fact, disappointment can lead people to abandon certain expectations and modify their goals accordingly. They can also prompt them to make greater efforts to achieve the desired goal by other means. Referring to some of the findings of psychoanalysis, which, unlike positive psychology, assumes that there are paradoxes in people’s lives that cannot be resolved or, above all, converted into something positive, he proposes that contradictions and ambivalences should be seen not as problems to be solved, but as a given that needs to be accepted and that reflection can help to distance.

In the final chapter, after noting the West’s loss of hegemony and a model of social evolution that took increasing material prosperity for granted, Andréas Reckwitz calls for a different kind of society, one in which individuals accept obligations to others and to society as a whole.

La fin des illusions : Politique, économie et culture dans la modernité tardive

Andrés Reckwitz

Traduit de l’allemand par Loïc Windels,

éditions de la Maison des sciences de l’homme. 22€

Illustration de l’entête : Andréas Reckwitz. Photo: © Juergen-Bauer

Vous souhaitez réagir à cette critique

Peut-être même nous proposer des textes et d’écrire dans WUKALI

Vous voudriez nous faire connaître votre actualité

N’hésitez pas, contactez-nous !