Rembrandt, beyond his person, beyond time and history, beyond the painter’s radiance, beyond his talent, which is so overwhelming that it cannot be defined, is a moment in our humanity, an unsurpassable emotion, a gaze that pierces us in his many self-portraits, a warm presence that accompanies us on our hazardous paths through life and teaches us to love, and above all, to live, yes, to live…

A long time ago, a prestigious collection of books on the Italian Renaissance was entitled Le Temps des Génies. Considering Rembrandt, I’m tempted to use this title to evoke the artistic effervescence that animated Holland, this small country in Northern Europe, in the 17th century, the aptly named Dutch Golden Age, and the genius is without a doubt Rembrandt.

The exhibition at Vienna’s Kunsthistorisches Museum, which contrasts Rembrandt and Hoogstraten, the master and his pupil, is particularly interesting. Already in terms of the number of works on display. It’s a definite and intelligent pleasure to see two artists in parallel, emulating each other, not in antagonistic competition, but in rigorous and demanding complicity.

What a joy it is, too, to see in one and the same place paintings by our revered master such as The Girl with the frame, from the Royal Castle Museum in Warsaw, which literally seems to be breaking out of the confines that constrain it. This painting was part of the collection of Karolina Lanckorońska, a Polish aristocrat, woman of courage and conviction, art historian, resistance fighter and combatant who was arrested by the Gestapo and sent to the Ravensbrück concentration camp. She fought against both the Soviets and Communists, who were murdering Poland’s intellectual elite, and the barbaric Nazis. She managed to leave Poland as a stateless person and, at the end of the war, donated her priceless art collection gathered by her family over the years to the Royal Castle Museum in Warsaw.

Let’s take a closer look at this Girl with the frame, observing the frontal positioning of the figure and the slightly oblique angle, a verticality befitting the character of this gentle-looking girl, dressed all in brown velvet, pearls in her ears, long auburn hair falling in braids over her bust, wearing a vast black beret that crowns her head, and carrying on her belt an oriental dagger in its shiny sheath of chased metal. Could she be a huntress ready to leap out of the frame of this painting that holds her back? The movement of her right hand is obvious, contrasting with the girl’s calm immobility. Her face and hands are bathed in light. A portrait of refinement, aristocratic and elegant.

Jeune-fille dans un cadre. 1641. panneau, 105.5 × 76.3 cm

© The Royal Castle in Warsaw – Museum

Photo: Andrzej Ring, Lech Sandzewicz

The Young Woman in Bed from Edinburgh, National Galleries of Scotland, all tender carnal warmth and restlessness, a fraction of time, where Rembrandt takes a story from the Bible (The Book of Tobit (5/7)) and turns it into a human event, not a banal one, the encounter between an elderly man and a young girl given to him as a wife by her father according to the Scriptures. We see only a brief moment, an infinitesimal space of time. The young girl, in semi-nudity, barely concealed by a nightgown that gives a glimpse – or rather, an image – of an opulent, virginal bosom, waits in the privacy of her bed, her left hand holding back a red curtain that conceals the alcove, for the husband who has been given to her.

1647. Huile sur toile, 81.10 x 67.80 cm (arched top)

Edingburgh, National Galleries of Scotland; presented by William McEwan 1892

© National Galleries of Scotland, photo: Antonia Reeve

We notice a curtain, or rather a rich drapery, like that adorning a baldachin, unintentionally creating a certain theatricality that the Caravaggio influenced painters would seize upon. This same curtain can be seen in The Holy Family (1646) at the Gemäldegalery in Kassel. This painting is quintessentially Rembrandt.

It’s no longer the Bible we’re talking about, but the sacredness of the human being, of the woman, and the religious references disappear to make way for the emotion of flesh and life, of the ephemeral and the tender, of the fragility of the moment, of the gaze and the timeless complicity between the figure painted by Rembrandt (all the more so for his self-portraits) and the viewer. The flesh, yes the flesh, the skin, fragile, changeable, sensual, trembling with desire, but also with fear and anxiety, a palimpsest that accompanies us, that lives and changes and transforms, that shivers or armors and serves as a screen for our ardor, our Dionysian thirst for knowledge, our impulses, our desires.

“Love is an impulse of the soul which in its essence detaches itself towards God in order to unite with His very high light”, said a medieval Jewish Aristotelian scholar and philosopher, Bahya Ibn Paquda בחיי אבן פקודה, an 11th-century Andalusian rabbi. We are standing at the heart of this mosaic spirituality that runs through Jewish and Christian teaching, that of the Bible, and that Rembrandt knew, as he was friends with many of Amsterdam’s Jewish families because he was received into their midst.

We are here in this coalescence, this fusion, this particle of humanity and eternity that creates transcendence. I’ve always wondered, as Giacometti did: “In a fire, between a Rembrandt and a cat, would I save the cat ?”. Yes, of course, but my heart would be broken.

Here we are, yes, and let’s not go any further for the moment into the unfolding of this magical exhibition, for we have already reached the very essence of Rembrandt’s eternity and uniqueness. His life, it should be remembered, is in itself a novel, a tragic story. There are many biographies of Rembrandt, and one of the best and most well-documented, albeit an old one, is by Marcel Brion. “I’m looking for a man ”, said Diogenes. Rembrandt is this man, the one who embodies respect and emotion, this tutelary, perhaps even paternal figure, and everyone will have their own interpretation.

The Kunsthistorisches Museum’s exhibition is awe-inspiring, thanks to the wealth of works on loan, and we’re still a long way from having seen it all.

1635 . Huile sur toile, 123.5 x 97.5 cm

London, The National Gallery; purchased through the Art Fund, 1938

© The National Gallery, London

Here is Saskia welcoming us, Saskia van Uylenburgh in Arcadian costume, also known as Saskia in Flora (1635), straight from London’s National Gallery. Rembrandt’s richly endowed wife, the mother of Titus, the son whose life was too short. Saskia the beautiful, the woman, the beloved wife, the time of joy, happiness, wealth and easy living. A portrait, a gift, something of grace and sentiment, a delicious tribute between passionate lovers, a representation influenced by the “antique”. When Saskia died, it was a descent into hell for Rembrandt, all the more so since the time of success and luxury, of abundance and lavish spending on porcelain, furs, jewels and carpets from the Orient was behind him after the scandal of the Night watch.

Kunsthistorisches museum, Vienne

His friends, clients and sponsors had all abandoned him, except for Amsterdam’s Jewish community, who welcomed him with open arms. It was in the synagogue, moreover, that he found models to depict the characters in his paintings in scenes from the Old Testament. As for his family circle, it was reduced to his son Titus and his benevolent servant, Hendrickje Stoffels, who also became his servant-mistress and mother of Cordelia, the little girl born of their union. Titus, a fine painter by the way, died a year before his father. Alone, all alone, his loved ones all gone, such was the difficult end of Rembrandt Harmenszoon van Rijn ‘s life , of whom only his first name, Rembrandt, remains for posterity.

panneau 78.8 à 60.8 cm, coupé en oval

Vienne, Kunsthistorische Museum

Rembrandt, the portraitist, as we have already seen in the preceding pages, has captured us with emotion in this exhibition, with this portrait of an old woman entitled Anna the Prophetess. Stunned and trembling, a woman, an old woman with wrinkled, parchment-like skin, an astounding quality of observation and graphic rendering, with the added serenity, solidity and light emanating from her person. In an inventory, this sumptuous portrait of an old woman was considered to be that of Rembrandt’s mother, as indicated in Bredius and Berenson1. The figure of Anna the prophetess appears in the Gospels of Luke

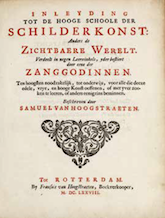

What do we know about Samuel van Hoogstraten ?

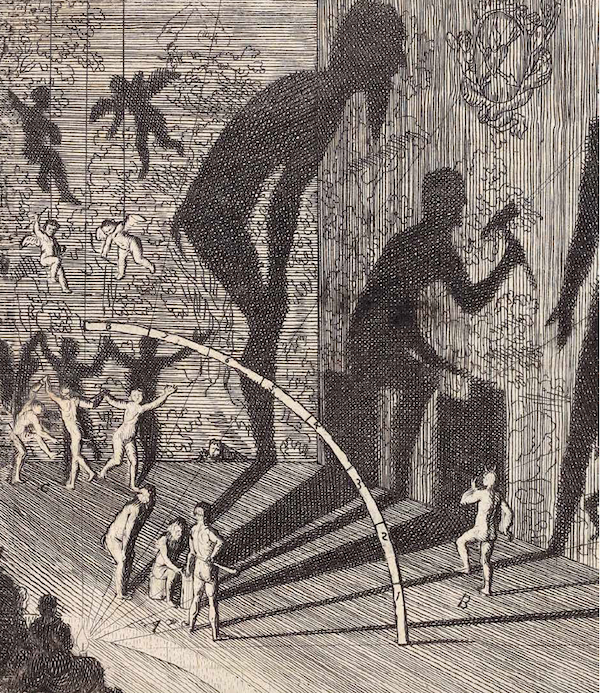

Not only Hoogstraten one of Rembrandt’s pupils, he also began working in his studio at the age of 15. He also wrote a treatise on painting that helped establish his reputation, Inleyding known in French as Introduction à l’Académie supérieure de l’art de la peinture : ou Le monde visible. 2

Munich, Staatliche Graphische Sammlung

A brilliant pupil, he assimilated his master’s lessons on both color and perspective. From Rembrandt, he learned in particular the ability to create a “houding” a Dutch word difficult to translate and found in the manuals of the time, but which corresponds somewhat to an illusionist rendering in a shallow spatial depth. Moreover, his work showed a capacity for flexibility that enabled him to move from one style to another, with what can only be described as a certain sense of humor; he was far removed from any ideological or even scholastic constraints on what was or wasn’t appropriate to paint or draw, and how to do it. Rather nice, isn’t it?

Huile sur toile 47.1 ~ 61.8 cm.

Dordrechts Museum,

190~ 145 mm. Amsterdam, Museum Rembrandthuis

Hoogstraten was fascinated (as can be seen in his treatise and, of course, even more clearly in his paintings) by the fine line between reality and illusion. Painting as the representation of an optical game, so to speak. It’s worth noting in this respect (and the remark is not accidental) that at the time, the Dutch were masters in the manufacture of lenses designed for both ophthalmology and astronomical purposes (see Vermeer’s The Astronomer, in the Louvre , for example).

The competition between master and apprentice is evidenced by the masterly execution of the illusion in related works in terms of composition and technique from the period when both artists were active in Amsterdam. Aside from his still lifes and trompe l’oeil, Hoogstraten took great pleasure in rendering perspective. It’s important to note that the concept of aemulatio, or competition between artists, was fundamental to 17th-centuryDutch art, and it was common practice for a master, such as Rembrandt, to rub shoulders with his pupils over a subject or a way of painting.

Toile sur panneau, 62.7 x 81.1 cm

Staatliche Museen zu Berlin, Gemäldegalerie. ©Christoph Schmidt

Rembrandt’s sublime St John the Baptist Preaching in the Desert, now in the collections of the Gemäldegalerie der Staatlichen Museen In Berlin, whose original model appears to be a lost painting by Pieter Lastman (1583-1633), is a good example of this community of painters, this emulation, this taste for competition, for exchanging know-how, for respectful rivalry between artists. The subject was common at the time, and shows the Baptist addressing the multitude who come to him to be baptized.

1650/75 Huile sur toile, 103 x 70 cm

Musée du Louvre, Paris Photo © RMN-Grand Palais (musée du Louvre) / Michel Urtad

Samuel van Hoogstraten was one of those great European artists who traveled from north to south and from court to court. Rembrandt, on the other hand, never left the Netherlands, like Shakespeare in England, who produced his work without ever leaving the kingdom. He stayed at court in Prague just after the end of the Thirty Years’ War. He even crossed the Channel and witnessed the Great Fire that ravaged London for a week in September 1666.

- Bredius and Berenson la référence incontournable pour la connaissance de l’oeuvre de Rembrandt

↩︎2. Ce traité est d’une importance majeure dans l’histoire de l’art et tout particulièrement dans la connaissance de l’œuvre de Rembrandt et des pratiques artistiques dans cette république des Pays-Bas du XVIIe siècle. Ainsi Samuel van Hoogstraten évoque son séjour dans l’atelier de Rembrandt nous donnant un aperçu unique sur le travail du grand maître, sa pratique de l’atelier, ses méthodes de formation et ses approches de la théorie de l’art

Ce lien extraordinaire entre les deux artistes occupe une place essentielle dans la littérature Rembrandt. Au début des années 1990, Ernst van de Wetering a commencé à interpréter l’Inleyding comme une source d’inspiration pour l’œuvre de Rembrandt.

Rembrandt-Hoogstraten

Color and Illusion

Exhibition in Vienna , Austria. Kunsthistorisches Museum, up to January 12th 2025

This text also exists in its genuine FRENCH version ( click on the flag)

Illustration de l’entête: Samuel van Hoogstraten. Vieil homme à la fenêtre. 1653. Toile 114,9×91,3 cm (détail) Kunsthistorisches Museum Vienne. Photo© KHM-Museumsverband

__________________

Vous souhaitez réagir à cette article

Peut-être même nous proposer des textes pour publication dans WUKALI

Pour nous retrouver facilement vous pouvez enregistrer WUKALI dans vos favoris

Contact : redaction@wukali.com

To support us, easy, your social networks !😇

Our best advertisement is YOU !

“