The bodies represented in the exhibition currently on display at the Maillol Museum in Paris, until March 5, 2023, conceived and co-organized by the Tempora agency, plunge us into a strange universe and question the status of the human body by sometimes maintaining a blurred boundary between the robot and the human being.

Hyperrealism, presented here under the sole aspect of the sculptural representation of the human body, is part of a broader movement that appeared in the United States in the 1960s in painting as a reaction to abstraction or other styles deemed too classical and inadequate to reflect the society of the time. If the body appears at the beginning of the movement as a product of the consumer society and a political and social fact, from the 1990s it becomes a means of psychic and emotional expression. From then on, artists will never stop questioning this relationship to reality, which is inseparable from a reflection on the body.

The term “hyperrealism” appeared for the first time at an exhibition organized by the Belgian gallery owner Isy Brachot in 1973 in Brussels.

Along a path comprising six sections organized by theme, providing the necessary keys to understanding each work individually, the artists selected at the international level (United States, Spain, France, Australia, Great Britain, Italy, etc.) offer us a new look at the evolution of the human figure. A sculpture by Daniel Firman Caroline (2014) opens the exhibition with the representation of a young woman in sneakers, dressed in a teeshirt and black jeans, whose head and arms are hidden under a green sweater. Her forearms leaning against the wall reinforce the impression of anguish that emanates from this work made of resin from casts, whose resemblance to a real human being confuses the visitor.

Collection Odile et Eric Finck-Beccafico

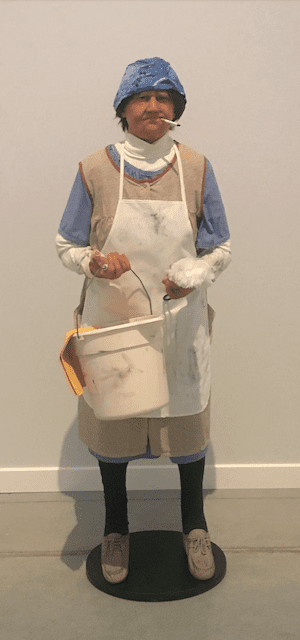

All the works presented in this exhibition question the human condition in the era of globalization, whether it be Tom Kuebler’s Ethyl (2001), a silicone sculpture showing an office cleaner, cigarette in mouth, bucket in hand, treated with humor by the painter, or Duane Hanson’s Two Workers (1993), showing two workers of the museum of the city of Bonn realized in bronze from casts but also of anonymous people met in a park such as Blue girl on Park Bench (1980) a work in which George Segal gives to a scene of the everyday life a melancholic tone by insisting on the loneliness in which is the contemporary man lost in a mass society. At the same time, Jacques Verduyn was also interested in everyday life, and in Pat and Veerie (1974) he presents us with one of its summer aspects, in which two women sitting in deckchairs sunbathe, entrenched in a disturbing solitude that questions the border between life and death.

Considered the pioneers of hyper-realist sculpture, Duane Hanson, John DeAndrea and Georges Segal chose to represent the body in a realistic way using various techniques such as casting on live models.

Other artists chose to model and apply polychrome paint to the surface of their sculptures or were inspired by photographic models.

Materials used include epoxy resins, fiberglass with added hair in John DeAndrea’s American Icon – Kent State (2015), a bronze made from a photo taken during an anti-Vietnam War protest on May 4, 1970 where four Kent State University students were shot by the Ohio National Guard, or Dying Gaul (2010) a work inspired by a Roman era marble in which DeAndrea expresses the emotional state of a withdrawn man.

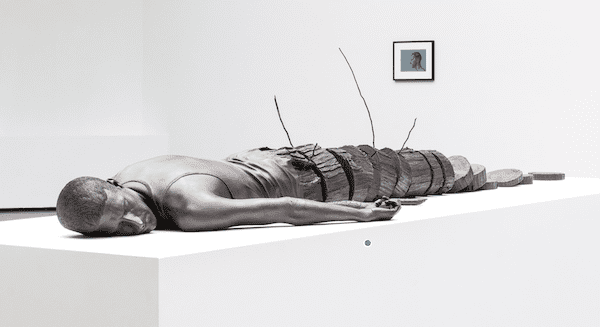

Duane Hanson uses clothing in Cowboy with Hay (1984-1989), a satire of the myth of the American cowboy presented both as heroic from a distance but which, as soon as one approaches it, reveals a more melancholic aspect. White marble is used by Fabio Viale in Venere italica (2021), a copy of Antonio Canova’s Venus Italica seen through a contemporary eye. Bronze is used by Fabien Mérelle in Tronçonné (2019) a tormented self-portrait of the artist’s face whose lower half of the body melts into a tree trunk.

Collection de l’artiste et Keteleer Gallery

Punctuated by short films that illustrate the creative process of the various artists, the tour leads the viewer to more disturbing works, some of which present body parts: three forearms emerging from a wall in Maurizio Cattelan’s Ave Maria (2007) in a provocative approach that takes on a blasphemous tone here.

Collection de l’artiste

Others offer bodies in small formats such as this particularly moving sculpture made of silicone and latex by Sam Jinks, Woman and Child (2010), where an old woman, with her eyes closed, hugs a baby to her chest in a gesture of contemplation. In this other small-format sculpture, Untitled (kneeling Woman) (2015) Sam jinks shows a young woman in a fetal position, head folded, hands clasped, touching in her vulnerability. (Heading illustration)

Collection de l’artiste

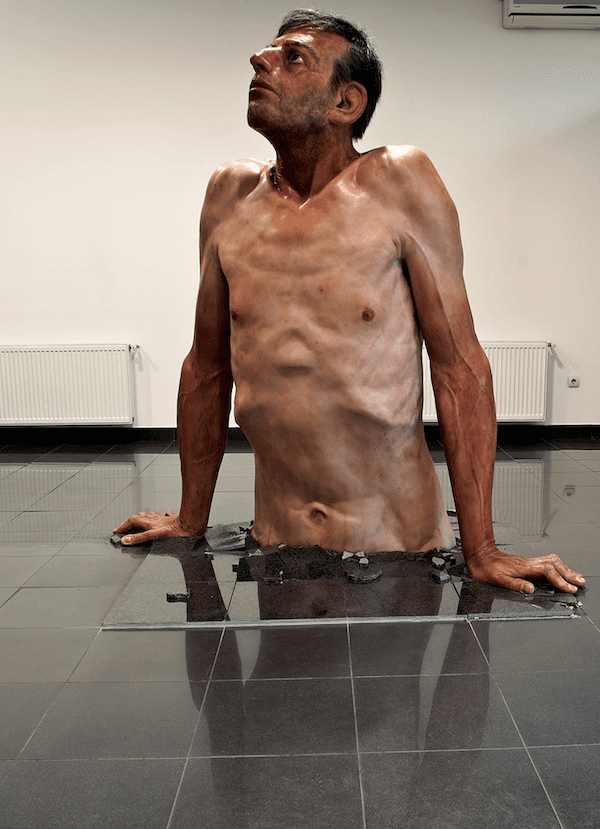

A similar emotional intimacy is found in Marc Sijan’s sculpture, Embrace (2014), showing the embrace of a middle-aged couple. Some works, on the contrary, are oversized, such as Zharko Basheski’s Ordinary Man (2009-1910), whose torso alone emerges from the ground as he anxiously scans the sky.

Collection de l’artiste

The question of the human future is at the heart of the artistic concerns of some sculptors, in the face of new technologies that claim to augment the body or even transform it at the risk of producing monsters. Patricia Piccinini with her hybrid creatures, deformed, at the crossroads of technology, nature and human gives us a glimpse of these genetic changes natural or caused by man in The Comforter 2010 where she questions the notions of beauty and ugliness, human and animal, natural and monstrous in this scene where a hairy little girl bends over the deformed baby she hugs and tries to console.

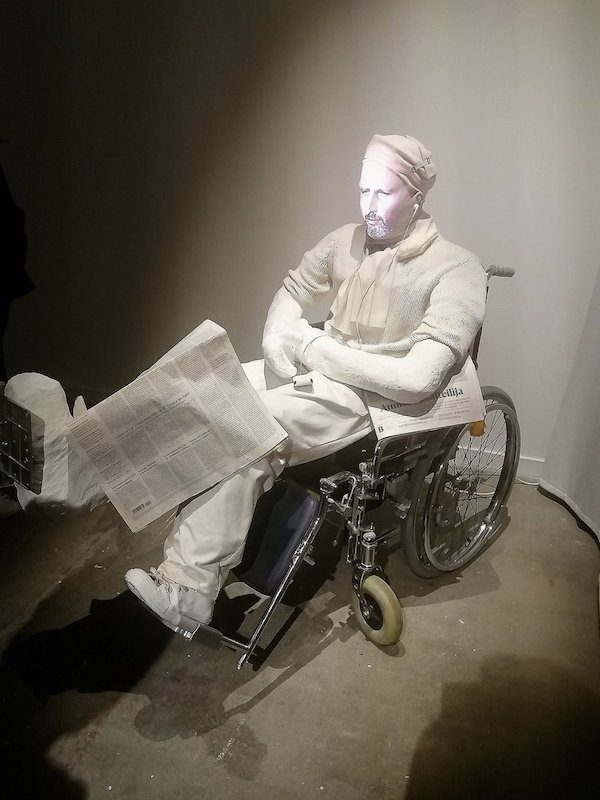

All the works gathered here pose in a different way the question of the border between life and death or announce the human future of genetic manipulations and humanoid robots. Daniel Glaser and Magdalena Kunz address this question in an obvious way in Jonathan (2009), the last work in the exhibition, in which they depict a man wearing a plaster cast, sitting on a wheelchair, with only his face exposed.

It comes to life thanks to a video projection and talks about the art market with an interlocutor absent from the scene. The work questions the moving borders between the living and the artifact, beauty and horror, it announces but also alerts on the emergence of a world of which the man would have lost the control by dint of wanting to push back always further the limits of the possible.

Exposition: Hyperréalisme ceci n’est pas un corps

à voir au musée Maillol.

61 rue de Grenelle. Paris

Métro: Stations/ Rue du bac, St Sulpice ou Babylone

jusqu’au 5 mars 2023.

Nocturne le mercredi jusqu’à 22h.

Une coproduction de Tempora et Institut für Kulturaustausch en étroite collaboration avec le Musée Maillol.

You wish to react to this critic

Maybe would you like too to propose us topics and articles ?

Don’t hesitate !

Contact us : redaction@wukali.com