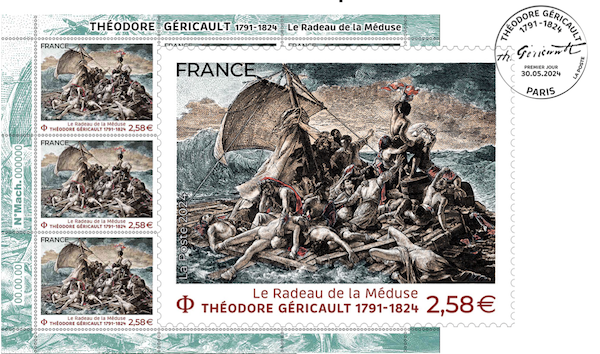

The French Post Office prides itself on the quality of its philatelic productions, the refinement of the stamps it issues, and the engravings and prints of its vignettes. It’s become a tradition, and a fine one at that, to celebrate French heritage masterpieces of art history through the production of stamps, and if, as everyone knows, Paris can’t be bottled, La Poste always achieves small feats of both technical and artistic skill in reproducing these paintings (most often) or other works of art in stamp form.

Indeed, since this is not a pipe, what we see on a stamp is a reduction of a work of art, and the engravers do a remarkable job. This is once again the case for this new stamp dedicated to the Radeau de La Méduse (The raft of the Medusa), engraved by Pierre Albuisson, a celebrated work by Théodore Géricault that we recently reviewed in WUKALI. It will go on sale on June 3, 2024.

About history first

The sinking of the colonial frigate La Méduse off the coast of present-day Mauritania on July 2, 1816 shook Restoration France to its core. Of the 150 or so passengers and crew who took refuge on a makeshift raft, towed by canoes and then abandoned by order of Captain Duroy de Chaumareys, fewer than fifteen survived. A total of 120 soldiers, 15 sailors and 8 civilians, including one woman, boarded the raft. We have already mentioned the players involved in this tragedy in our article on the subject.

This drama was immortalized by Théodore Géricault (Rouen 1791-Paris 1824) in one of the Louvre’s most famous paintings, Le Radeau de la Méduse, unveiled at the 1819 Salon. The work initially raised questions, shocked and disturbed the French public at the Salon, who only considered the news item, incapable (or uneducated) of considering the pictorial masterpiece, the work itself. Incapable, then, as in other times and places, others were scandalized by Caravaggio’s Death of the Virgin (1600) or Rembrandt’s Flayed Ox (1655). “Realism” is a word for fools. And we’re only talking about painting here; what would we say about literature, Sade, Flaubert, Baudelaire, Zola, Mirbeau, Beauvoir… and we could go on!

In his early years, Géricault devoted himself to painting horses, his passion, and military themes. Returning from Italy in the autumn of 1817, he was in search of new topical subjects. The atrocious assassination of the former magistrate Fualdès in Rodez (his throat was cut and his body thrown into the Aveyron) inspired the idea of a large-scale composition, which was eventually abandoned. For his first major work, he chose the Medusa affair, fascinated by the account of two survivors.

Rather than the sinking of the frigate, he depicts the raft and its passengers, abandoned on the open sea. In rags, some agonize among the corpses, while others rise to their feet, catching sight of a ship, their last hope of survival.

The composition was perfected using wax figures placed on a model of the raft, made at Géricault’s request by the former carpenter of the Méduse. Turning his studio into a morgue annex, Géricault painted severed heads and limbs from life, observing the ravages of disease in hospital. On the Normandy coast, he made studies of the sky and sea. Epic and terrifying, the final work, 7 m long, baffled the 1819 public. A tragic vision of human destiny, it has established itself as one of the major works of Romanticism, with universal appeal.

Comparative analysis

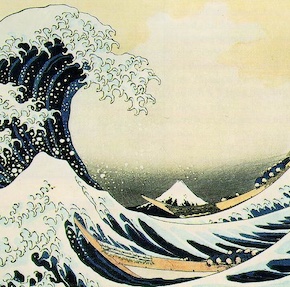

Hiroshige 歌川広重

Looking at Géricault’s depiction of this human tragedy, and especially his vision of it, one cannot help but think of a comparison with a completely different and, above all, totally unrelated work: Hiroshige’s The Wave, painted in 1831. Indeed, this work by Japanese painter Utagawa Hiroshige 歌川広重 (1797-1858), also known as The Great Wave of Kanagawa 神奈川沖浪裏, (Kanagawa-oki nami-ura), in addition to this impressive, inspired and lyrical vision of the wave itself, shows Mount Fuji in the center and on the right-hand side on the one hand, and sailors sighing in a frail boat tossed violently by the waves on the other. First of all, let’s underline the time difference between these two paintings: Géricault’s Medusa, 1819, and Hiroshige’s Wave, 1830 or 1831. As far as we know, Hiroshige never had to know about Géricault’s painting, yet his genius, which is also that of layout to use a convenient vocabulary, positioned Mount Fuji and then the skiff with its rowers in two strategic points. Mount Fuji, that quiet strength, that serenity and power, that matrix mystery of Japanese society, that reference point, and then the rowers, human dust struggling on the threatening, aggressive ocean, battling against Nature’s raging elements. In other words, a kind of metaphor for Japan, as we think today of the Fukushima disaster.

It is in any case interesting to consider from a purely intellectual point of view how two worlds alien to each other can meet, merge, mutually enrich each other by a certain force of Fate. This is the very meaning of art history. But we could extend this to physics and astrophysics!

More than ever, as some of WUKALI’s columnists and art historians like to talk about, these paintings evoke the psychological center. Today, we’d say subliminally, and I’m tempted to add, conscious of the anachronism of the subject, in a totally psychoanalytical way. Indeed, and you need the eyes of a sparrow hawk to see this in the painting, even though it’s large and unusual, the shipwrecked sailors stare in despair at a sailboat in the distance on the right, unaware of the drama unfolding.

To survive, the shipwrecked men will engage in cannibalism, for they lack everything, starting with water to combat thirst – an unbearable paradox in this liquid universe – and food, of course. Only 15 men escape the tragedy, but 5 of them don’t survive, and the atrocious truth is not known until much later.

A little stamp, a little nothing and the world comes alive again

We’d left for the open sea, for that cruel Oceano Nox, but now we’re back to the minimalist dream of an excellently crafted stamp celebrating Théodore Géricault’s Raft of the Medusa. So, art is at the heart of humanity, and even if ill winds seem to be blowing us away from it, unconsciously and transcendentally, everything brings us back to it – let’s hope so, at least!

Création et gravure : Pierre Albuisson

Impression : taille-douce

Format du timbre : 52 x 40,85 mm

Présentation : 9 timbres à la feuille

Tirage : 610 200 exemplaires

Valeur faciale : 2,58 € Lettre Verte 100 g

Conception graphique timbre à date : Aurélie Baras

Création et gravure Pierre Albuisson, d’après l’œuvre de Théodore Géricault, d’après photo de Luisa Ricciarini / Bridgeman Images.

To contact WUKALI, very easy : redaction@wukali.com