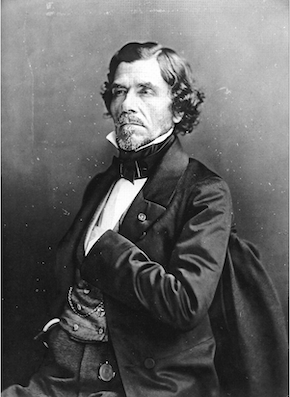

In 1851, Eugène Delacroix (1798-1863) was commissioned to decorate a chapel in the Saint-Sulpice church in Paris. After some confusion over the choice of chapel, he was commissioned to decorate the “Saints-Anges” chapel. Given the scale of his current projects – the Chamber of Deputies, the Senate, the Galerie d’Apollon in the Louvre – the artist didn’t begin his studio preparations until 1855.

His health was declining: he was suffering from tubercular laryngitis, an incurable disease at the time. As a result, he had to stop work several times. It was not until 1859 that he was able to resume his work in earnest. In 1861, this masterpiece was finally completed. The inauguration took place on July 21 of that year. Few understood the power and depth of this artistic testament. Exhausted, the painter died two years later.

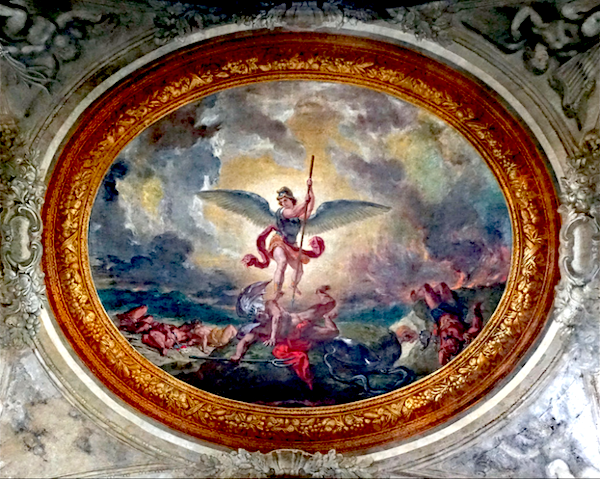

The ceiling of the chapel shows “Saint-Michel terrassant le démon” (Saint Michael overcoming the devil). It is a marouflaged canvas. The sides: “Héliodore chassé du temple” and “La lutte de Jacob et de l’ange” are mural paintings, in oil and wax,** on a plaster preparation.

At first glance, “Saint-Michel terrassant le démon” displays similar rhythms to “Apollon vainqueur du serpent python” (see Galerie d’Apollon in the Louvre): behind a Saint-Michel with angel wings spread, a fiery sun of supernatural yellow floods the scene, affirming the triumph of good over evil. Clouds and storms fade in the face of this divine illumination, carrying with them the putrid stench from the depths of the unconscious.

In the lower part, we recognize a Satan, with diabolical wings, wearing the crown of Hell. He collapses, dropping his pitchfork, his shield already on the ground. He is pierced by the vengeful spear, dragging with him the foul serpent, which tries to flee in a desperate retreat. Two dead warriors can be seen on the right. On the left, also dead, are three Amazons, recognizable by their bows and arrows. A hostile sea of oil surrounds this demented battlefield. At either end, horrific black fumes billow from volcanoes in cataclysmic eruption. It’s the triumph of light over darkness. The extraverted reds of the saint’s and demon’s garments, the heavy blues, divine yellows and deadly ochres set this apocalyptic scene ablaze.

137,5 × 102 cm. Photo Wikipedia

It’s striking that the artist has followed a compositional scheme similar to that of his “Apollo Conquers the Python Serpent”, one of his earlier decorations. With one exception: the painting is centered on the spear and the Michel-Demon ensemble, whereas it was centered on Apollo and Diana in the Louvre. There’s no denying that Delacroix was inspired by the position of Saint Michael in Raphael’s painting in the Louvre. But while the painter appealed to Raphael and the Venetians, with Tintoretto in the lead, the pictorial expression of this molten world belongs to him alone, owing only to its creator what characterizes it. That said, we can’t say that this is a proven success, far from it: the viewer doesn’t enter into the work, the artist having failed to make it credible. Structurally, the painting lacks cohesion.

The two side panels, on the other hand, are timeless paintings whose universality is universally recognized today.

Heliodorus driven from the temple measures 715x485cm. The subject is biblical: it belongs to the Book of the Maccabees. Raphael had interpreted it in his time at the Vatican. Delacroix makes no reference to it.

Photo Wikipedia

Two groups of figures are defined: on the first floor, in the left foreground, a mysterious, vengeful angel-rider rides bareback on a horse standing on its hind legs. He strikes the tax collector with his hoof. In the rider’s right hand is a golden sceptre. Two pedestrian angels accompany him, violently flogging Heliodorus with rods. Their energy is palpable and impressive. One is seen parallel to the rider, the other vertically above the soldier, forming a complete perpendicular.

©photo Mairie de Paris

The latter was inspired by Tintoretto’s “Miracle of San Marco” (Accademia Gallery, Venice). On the ground, the jewels and silverware that the desecrators of the temple wanted to seize; they form a still life in which the smallest object is marvelously painted. On the right, three soldiers carrying precious objects try to escape. At the far end, a large opening appears to lead to a peristyle.

Two distinct groups are upstairs: the first on the right is made up of the high priest, four Levites and two women; on the left, the second is made up of four people, a man, two women and a child; a colonnade opens behind their backs. All are stunned by the incredible event. Behind the high priest, a blue curtain opens onto another flight of stairs, this time empty. Two female forms can be seen at the entrance to the second level.

On the staircase, a woman implores Heaven. Access to the upper level seems slow and difficult, so much so that the stone steps seem to mark a caesura. There’s a dichotomy between the miracle below and its spectators at the balustrade.

The staircase is a link between the two, reserved for those who are able, in every sense of the word, to climb it. This ascent seems somewhat supernatural: only God’s chosen Ones will be able to reach the ultimate level.

Eugène Delacroix defines a highly geometric organization of space: with horizontal and vertical guiding lines. But it’s around the majestic central column that everything revolves: it divides the volumes into two vertical parts. A high wall connects the two enormous central pillars, while another wall closes off the space to the left of the staircase. The architecture becomes the heroine of the work, a character in its own right in this scene, as in Piranese’s engravings, such as the “Roman Antiquities”.

In both cases, the ceilings are elongated in such a way as to expand the pictorial space, appearing to be pushed back to the horizon. This effect is echoed by Van Gogh in his famous painting “L’enclos de l’asile de Saint-Rémy vu depuis la chambre de l’artiste”.

All the architectural elements are covered with decorations occupying their entire surfaces. These are sumptuous, almost lavish. This highly realistic reconstruction of biblical archaeology by a painter is exceptional. The local color is very delicate, superb and at its most intense (the exact definition of color). The gleaming hues of turquoise, violet, purple and gold are the logical consequence of the artist’s magical brilliance and perfect transparency. The rendering of materials further accentuates this effect: silky fabrics, luminous goldsmithery.

All these novelties are the pure creations of a genius named Delacroix, who here reaches the pinnacle of the art of painting by imposing an absent divine presence. The oxymoron is easy to explain: just look at the way the magnificent staircase hangings, in translucent pale red, shake. It’s heavenly wrath being unleashed: the spectator feels it so intensely that goose bumps seize him. Even the material form of the main curtain, separating the two hemispheres of the painting, shows this: a sort of prehistoric open maw, a welcome pareidolia, appears as a result of the reversal of a small part of the hanging (pink and white) in relation to the whole (red).

The struggle between Jacob and the Angel measures 751x485cm. This scene forms a triptych of unique perfection: two gigantic oak trees, at the top of a small mound, separate the caravan, winding along on the right, from the man’s fight with God’s messenger.

© Ville de Paris /COARC – Claire Pignol

The magnificence of the trees, transmuted into human beings witnessing the miracle, surpasses all fiction. The positioning of the trees – steeply tilted to the right and centered at a slight angle – gives each a different personality: the first has roots like tiger or lion claws digging into flesh, a powerful curved trunk and an arborescent branch reminiscent of little running legs; the second has a magisterial trunk, worthy of ancient Jupiter, and branches that reach for the sky. Their leaves occupy the entire upper part of the picture. These are two centuries-old oaks in the Sénart forest, which inspired Delacroix: he often came across them on his solitary walks from his country house in Champrosay. They were known as Chêne Prieur and Chêne d’Antin.

Everywhere the vegetation is luxuriant. Every tuft of grass seems alive. To the far left runs a stream, while to the right the caravan stretches out endlessly: in the lower right are individualized horsemen, dromedaries, porters and sheep; in the upper left, small dots of men and beasts enter a steep defile between two hills; they eventually disappear into the distance.

All this creates a racket that the viewer doesn’t notice: he remains under the spell of the gentle atmosphere…until he sees the figures clashing on the left. This landscape is Delacroix’s finest. It is also one of the most beautiful in the history of painting.

Jacob lunges at his adversary with all his muscles flexed. His physical power is formidable. Resisting this attack seems impossible for a normal man. But in front of him, the Angel, without the slightest effort, hits the human in the thigh nerve and paralyzes him. As much as Jacob’s bestiality is obvious, the Angel’s calm, gentleness and even indifference are of a celestial nature. The former is a natural being, while the latter is divine in nature.

At their feet, a pile of clothes and weapons that are easy to decipher. They form a still life, a counterpart to Heliodorus’ precious objects.

Photos: Steven Zucker

To read these lines, one might think that the painting is badly composed: that the three scenes don’t create a true whole. In reality, the eye analyzes each of these three acts one by one, before bringing them together in a synthetic vision whose unity is its primary quality. This implies a notion of duration to take complete visual possession of the work. With experience, the analyst knows that introducing the dimension of time into a painting is not within the reach of just anyone. Only the most talented artist, let alone a genius, is capable of doing so.

Let’s turn now to the rendering of colors: they are fairy-like, as if miraculous, under a soft luminosity that accentuates the sensation of a mirage, or even an oriental tale, that insinuates itself into the observer’s mind. Ochres, blues, reds, purples, violets and greens are the instruments, always in unison, of this unique symphonic orchestra. It’s an enchantment for the mind as well as the eye. The effect is so strong that it becomes an almost gustatory pleasure. This specific alchemy is the result of a lifetime: that of the artist’s thoughts, his vision as a director, and the hard work of his hand wielding the brush.

These two marvels of two-dimensional art were politely hailed, sometimes sincerely praised by open-minded critics,*** but little applauded in their day. The artist’s message was too far ahead of its time. With the patina of time, external reality gave way to intrinsic truth.

René Huyghe**** was the man who best explained Delacroix’s intellectual journey, which took him to the higher plane of harmonious spirituality, where the soul finds its balance. This is demonstrated by the melodic composition, expressive staging and sovereignly beautiful color tones of these two paintings.

But “Paradise” remains inaccessible to human beings, however transcendental they may be…

** la technique de la peinture à la cire, dite aussi à l’encaustique, consiste à délayer les couleurs dans de la cire d’abeille fondue( le liant). Elle était connue dans l’antiquité. Au 19ème siècle, on utilisait aussi de l’essence de térébenthine.

*** Baudelaire fut l’un d’eux.

****Voir l’article que nous lui avons consacré dans Wukali.

– René Huyghe, historien d’art généreux et parfait honnête homme

Différents articles consacrés à Delacroix et parus dans WUKALI

– Eugène Delacroix, fils illégitime de Talleyrand

– De qui vraiment Eugène Delacroix est-il le fils

– Le premier livre de peintre, Faust de Goethe illustré par Delacroix

– Regards croisés sur la Chasse aux lions d’Eugène Delacroix

– La barque de Dante, oeuvre par laquelle Delacroix se fit connaître

– Actualité des carnets de voyage de Delacroix au Maroc

– Une peinture de Delacroix volée il y a un an dans une grande galerie parisienne a été retrouvée

– Un portrait de George Sand par Delacroix vendu aux enchères

– L’autoportrait au gilet vert d’ Eugène Delacroix

– Courbet et Delacroix font l’actualité

– Huit mois avec sursis pour la femme qui a tagué la Liberté guidant le Peuple

WUKALI est un magazine d’art et de culture gratuit et librement accessible sur internet

Vous pouvez vous y connecter quand vous le voulez…

Pour relayer sur les réseaux sociaux, voir leurs icônes en haut ou en contrebas de cette page

Contact ➽ redaction@wukali.com