In recent days, the University Milano Bicocca has asked the Italian writer Paolo Nori to postpone the course he was to give on Dostoyevsky “to avoid any form of controversy in this moment of high tension“.[1]. In a video posted on Instagram, Paolo Nori, on the verge of tears, lamented that being a Russian was now considered a crime, even though the Russian in question had been sentenced to death in 1849 for belonging to a progressive circle opposed to the tsarist regime. As we know, Dostoyevsky’s sentence was only commuted on the day of his execution, an ordeal that was to mark him for the rest of his life. He was sentenced to the Siberian prison where he lived among common prisoners for four years before his exile was extended as a private. He then befriended a local magistrate with whom he was able to converse and share the books that the magistrate provided him.

In a recent book, the Hungarian philosopher Laszlo Földényi imagines that Dostoyevsky became acquainted with Hegel’s Lessons on the Philosophy of History in this way. Very schematically, one remembers that Hegel professed that through the jolts of history a Spirit, a universal reason, is gradually established. The great conquerors, while seeming to obey their passions, are the unconscious instruments of this Spirit. Thus, having seen Napoleon at Jena in 1806, Hegel called him “the soul of the world”.

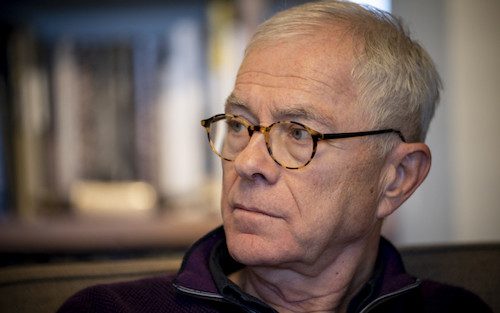

photo : Valuska Gábor

However, in the preamble to the text that Dostoyevsky held in his hand, Hegel specifies that he excludes certain regions of the world from this universal movement, starting with Siberia, a territory that is unsuitable, like Africa and other primitive regions, for becoming a particular actor in history.

Laszlo Földényi [2] imagines the scene and shows us Dostoyevsky immediately bursting into tears. Thus, Siberia, its inhabitants, its prisoners, himself were not part of humanity! Thus, his life, the ideas that had earned him his condemnation, his suffering for so many years counted for nothing in the history of the human race.

Földényi suggests that it was after this crisis that Dostoyevsky developed his own vision of human history. In his eyes, true humanity is the exact opposite of what Hegel thinks. Hegelian rationalism is not a rattle for intellectuals. True humanity, the one he will testify in his works, is not carried away by the flow of a superior Reason, for which individuals do not count, even if they perish by thousands. On the contrary, it is made of the singular destiny of each person with its batch of sufferings, anguishes, particular paradoxes, in the middle of the absurd tumult of the events.

The present invasion of Ukraine by a dictator convinced to write history would easily take its place in the Hegelian logic. And it would undoubtedly draw new tears from Dostoyevsky. His thoughts would painfully go to all those unfortunate Russians abused by propaganda, to those young soldiers who phone sobbing to their mothers, to those isolated resistance fighters, hunted down by the police, imprisoned.

One of the worst excesses of war is the indiscriminate transformation of the enemy into a monster. If we want peace to be restored, far from discrediting an entire people, we will have to rely on all men of good will, regardless of which side the madness of the powerful has divided them for a time.

[1] Information du Courrier international extraite du Corriere Della Sera du 3 mars 2022.

[2] FOLDENYI L., Dostoïevski lit Hegel en Sibérie et fond en larmes, Actes-Sud, 2017

Original text in French, click on the flag top of page

Dernier roman d’Armel Job

Un père à soi

éditions Robert Laffont. 20€