For four or even five decades after the Second World War, a whole range of musical creation by Jewish composers proscribed by Hitler’s regime was obscured. Yet their works were written and performed under very special conditions in the concentration camps, especially in Theresienstadt, also called Terezín, located 50 km north of Prague. Until the works of these musicians who composed them in their ghetto or before, and whose memory was gradually honored, were gradually resurrected.

In the Terezín camp in Czechoslovakia, an intense and high-level musical and cultural activity developed, the justification for which has been analyzed in the course of research and sociological studies carried out long after the tragic events.

In the sphere of music alone, and without going into other aspects of the question, the reasons for this surprising ostracism are more than surprising. In this respect, we can consider that these reasons come from the fact that after 1945, progressive theories of contemporary music were privileged. In particular, in the tradition of atonalism, dodecaphonism and serialism developed by the disciples of Schoenberg and the Vienna School, while on the other hand, works written and performed by Jewish composers in the camps, some of which were of unquestionable artistic value, were neglected or even ignored.

Opera according to an inverted dialectic of life and death

This is the case, among others, of an opera by Viktor Ullmann, “Der Kaiser von Atlantis, oder Die Tod Verweigerung” (i.e The Emperor of Atlantis or the refusal of death). The composer, who was a disciple of Arnold Schoenberg in Vienna, had been seduced by the theories of anthroposophy developed at the beginning of the 20th century by Steiner, studying the relationship between the human being and the universe, hence his first opera “Der Sturz des Antichrist” (The Fall of the Antichrist) after Nietsche, which prefigures the theme of the tyrant oppressor of art, science and religion. In contrast to the realistic opera, it is a sung allegory that is a parody of reality.

In the end, it allows us to perceive a prefiguration of the future, the strength of which can be measured by the subliminal reading that its listener may have, as the work, of a testamentary nature by Victor Ullmann, is a densification of the artist’s forces in his struggle against an existential revocation.

Thus, the opera was composed in 1943 in the Terezín camp, staged until the day of its dress rehearsal in September 1944, but was never given its first public performance in the camp, as were other of his musical compositions. A mystery? A month later, Viktor Ullmann was evacuated with his wife and his librettist, the young poet Peter Kien, to the crematorium at Auschwitz where they were all gassed. It was October 17, 1944. The day before, with them, many deportees, crammed into the same railroad convoys, suffered an identical fate.

It took more than thirty years after the war before Viktor Ullmann’s opera, whose score he had entrusted to the company and which had been found almost miraculously, was premiered at the Amsterdam Theatre in December 1975. Now produced in many theaters around the world, it was premiered in 2004 at the Opéra national de Lorraine in Nancy and at the Cité de la musique in Paris, directed by Charles Tordjmann. Ullmann’s work was revived in the same production at the Théâtre de Luxembourg and at the Théâtre de Caen. Other productions of this opera multiplied everywhere, including one of the last, played in 2013 in Reims in the direction of Louis Moaty, as well as at the Athénée in Paris, Niort, Poitiers, Massy … In 2010, the “Cabaret Térézin” had, at the Théâtre Marigny in Paris, mounted a session of songs and melodies given at the camp.

In 2013, the singer Anne Sofie Otter paid a tribute to Terezin, and recorded a DVD of the popular songs that were played in the camp (Refuge in music). In June 2013, the Cité de la Musique in Paris dedicated its 6th Biennial of Vocal Art to Viktor Ullmann, and the official ceremonies in Lyon included those on the camps, “Pour que vive la mémoire” (So that the memory lives on), in this year of the 70th anniversary of the Liberation in 2015. In addition to books on the camps, films have been made including those, evoking Terezin, by Claude Lanzmann “Un vivant qui passe” then, in 2013 “Le dernier jour des injustes“.

Terezín – the spark that set the First World War on fire…

This is a strange and sinister picture of that antechamber of death that was the fortress of Terezín, which housed the Nazi transit camp for Jews, and to evoke some particularly dramatic cases of composers, conductors, musicians, singers and child choristers, whose artistic faith and commitment had something irrepressible and pathetic.

The name of the garrison town of Theresienstadt, which owes its name to the Austrian Emperor Joseph II wanted to honor the memory of his mother, Empress Maria Theresa. The town was made infamous by the fact that its fortress housed the Serbian nationalist student Gavrilo Princip, who murdered Archduke Franz Ferdinand of Austria and his wife in Sarajevo in 1914, thus triggering the First World War, until his death in 1918.

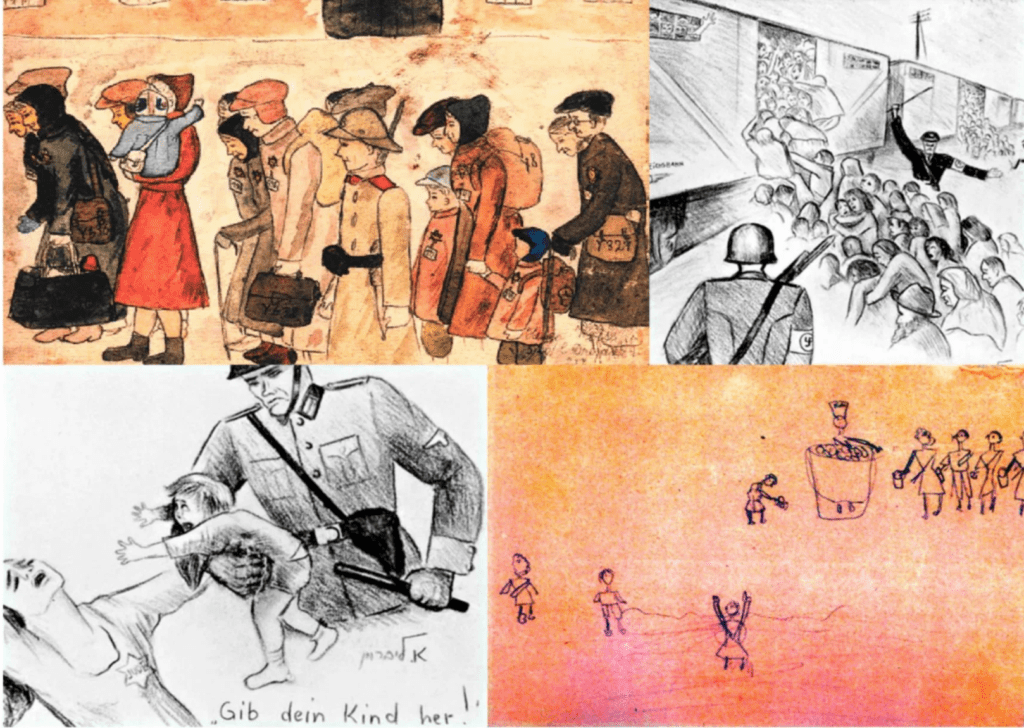

As soon as Prague and Czechoslovakia were invaded in March 1939, the Third Reich took the same segregationist measures that the Nazis had imposed on the Jews of Germany, Austria and the other territories they occupied. This policy, fomented as early as 1933, was aimed at purging what the Nazis called “musical Bolshevism“, a reflection of the formalism condemned at the same time by the Stalinist Russians.

This concept was applied, for example, at the creation of “Transfigured Night“, a score by Arnold Schoenberg, and the most virulent criticisms were levelled at the creation of the opera “Wozzeck” by Alban Berg, the composer being described as “the poisoner of the fountains of German music“. This shows the extent to which anti-Semitism was rampant in the circles of the Weimar Republic, the Republic of the Jews, it was said!

Worried about the turn of events, renowned soloists, conductors, composers and orchestral musicians, Jews and non-Jews alike, who were prosecuted under the Third Reich, left the country as soon as they perceived the harmful effects of the regime. Several Viennese composers moved to the United States, including Arnold Schoenberg as early as 1933 (he had been dismissed as professor of composition at the Berlin Conservatory by the Nazis). So did Erich Korngold in 1934, the German Kurt Weill in 1935, Ernest Krenek and Alexandre von Zemlinsky in 1938, and the Austrian violinist Fritz Kreisler in 1939.

The German composer Paul Hindemith, (who was not Jewish), took refuge in Switzerland, the Pole Norbert Glanzberg was protected during the war in the south of France thanks to the interpreters of his songs who were French singers like Edith Piaf, Tino Rossi, Marie Bell, etc… But the majority of the Jewish artists who remained in their country, underwent this immoral witch hunt.

The cynical subterfuge of a chic pseudo-spa !

The diktats aimed at controlling the intellectual and artistic life of the conquered territories were immediate, Goebbels, president of cultural affairs of the Third Reich, reorganized all artistic professions by excluding Jews. In 1940, the Gestapo transformed the fortress of Terezín into a prison. In 1941, during a meeting attended by the executioner Adolf Eichmann, the SS decided to found a model Jewish colony, mainly for Jews from Germany, Austria and Czechoslovakia.

In 1942, they decreed the double status of the fortress: a transit camp for the Jewish people of the Protektorate of Bohemia-Moravia, but a decent ghetto for the “Prominenten“, i.e. the privileged. They were assured that they would return home every weekend and that they should encourage their fellow believers to do the same. To disguise the reality, Nazi propaganda had even cynically described Terezín as a “comfortable retirement home” and even a “chic spa”!

All of this was, of course, a vast mystification. For in the plan of the concentration camp regime, the fortress of Terezín was indeed a sorting center for the gas chambers, mainly in Auschwitz.

The Jewish chairman of the camp’s Council of Elders was aware of the existence of the crematoria, but imagined, as he had been led to believe, that Terezín was a privileged and safe place, allowing its occupying artists to escape what was not yet called the Final Solution. This was not true, of course.

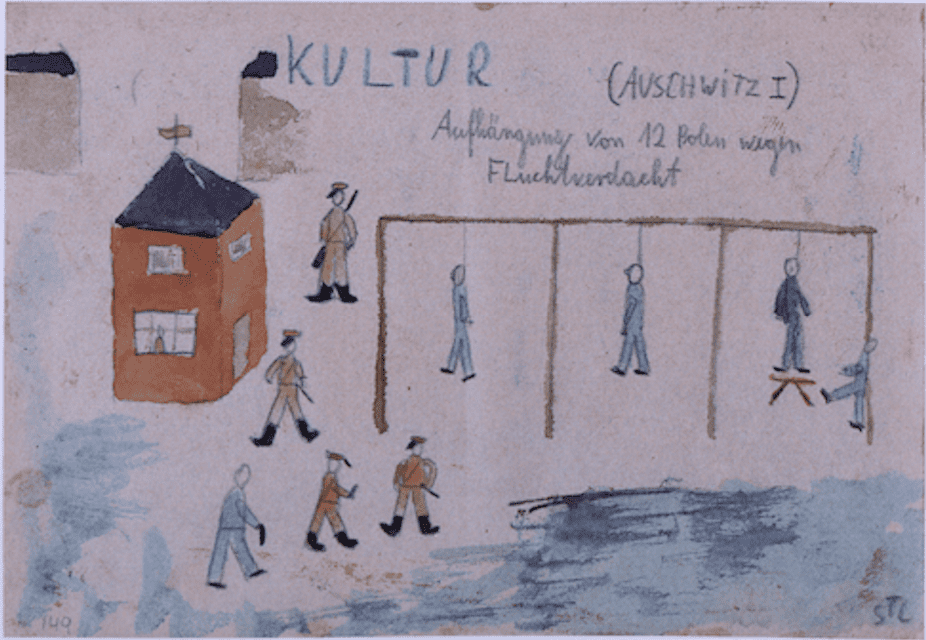

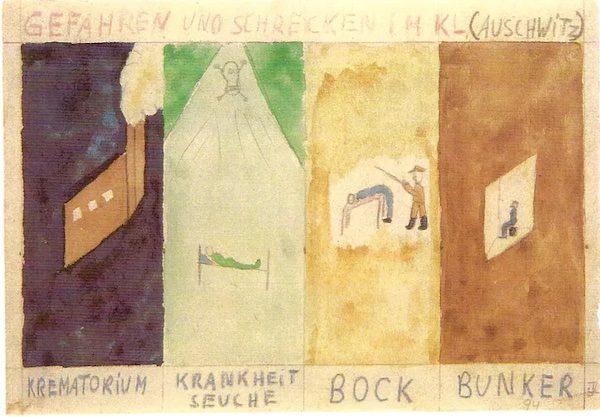

The drawing is entitled:”KULTUR”

Estimates vary according to the censuses carried out, but overall, we can evaluate the number of Jews who passed through this camp between 1941 and 1945 at 140,000, where 33,000 prisoners died, 87,000 were deported to other extermination camps and only 17,000 escaped. And of the 15,000 children detained, it has been said that about 100 escaped the crematorium.

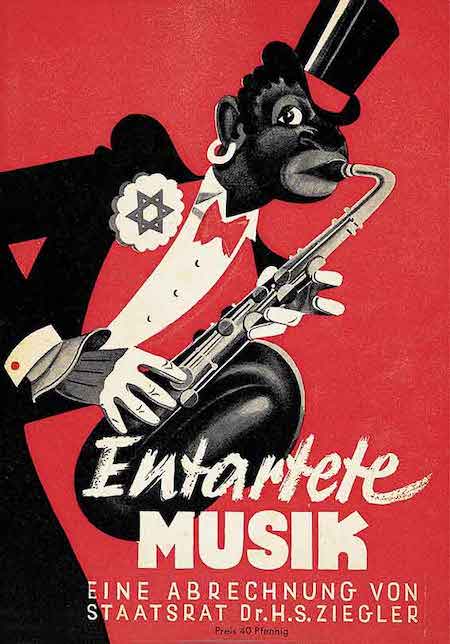

Entartete Musik or degenerate nazis?

The drastic measures imposed on Jewish artists resulted in a halt to their human and especially cultural activities. Actors were forbidden to perform, musicians were forbidden to play or teach, and even to own an instrument. Some performed under a false name and risked death. Publishers were ordered not to print any more Jewish music and composers wrote only “degenerate music“.

The scores of composers belonging to this category were burned, including those of Kurt Weill, the author of “The Threepenny Opera“. This was the application of the measures of which the Düsseldorf exhibition of 1938, following that of Munich in 1937, had been a shameful illustration.

The Entartete Musik included (independently of the works of dead composers, like Felix Mendelssohn, Gustav Mahler or Jacques Offenbach), three categories of music: 1°/ the avant-garde music, atonal or dodecaphonic, that is to say that of the School of Vienna of Arnold Schoenberg, Alban Berg and Anton Webern, as well as:

1°/ any composition pertaining to contemporary research music that was not in the imposed German classico-romantic line,

2°/ jazz, considered as a music of savages whose poster exhibited at the exhibition showed a black saxophonist stamped with the Star of David,

and, 3°/ the popular music known as proletarian.

Astonishing paradox and clever stratagem

The astonishing paradox is that music written by Jewish composers was formally forbidden in the entire Third Reich and in the countries it had annexed, whereas the music produced more specifically in the Terezín camp by the renowned Jewish artists who were captured there was authorized and then widely recommended and played in the camp on the same basis as the music of non-Jewish composers.

Another paradox is that the practice of music in the camp was first outlawed, then suspected, then tolerated. And, finally, it was vigorously encouraged by the authorities of the Third Reich!

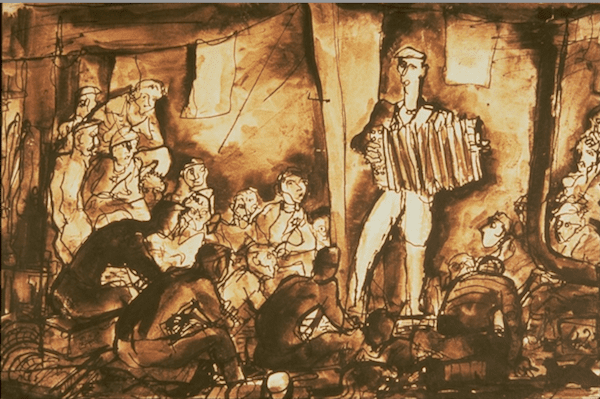

A clever ploy. At first, the Jewish internees who were part of the very first convoys that converted the citadel into a camp sang popular songs and Hebrew melodies on the sly in the evening. They soon formed a small underground vocal group. Then, little by little, they brought musical instruments under the cloak. The prisoner-musicians formed a small ensemble, then an orchestra, and gradually organized more or less confidential concerts. The Nazi leaders soon detected them, but instead of boycotting them, they encouraged them, and then made them official, to the point of putting symphony concerts on the program, which they gloried in, knowing full well that the performers who played them did not know that they were there on probation.

And above all, it was a way for the SS to justify itself and to display a brand image: “You see, here we protect Jewish musicians“. If, in Terezín, music served as a support for Nazi propaganda and as a means of promoting the regime, it was, on the other hand, a means of domination in other camps.

In Auschwitz, the Nazis annihilated any desire among the prisoners, the musicians were at the mercy of the SS and had to play in the streets in the morning and evening to accompany the commandos, these prostrate musicians having become “miserable automatons“, as described by Primo Levi, the well-known survivor of the Shoah.

In Terezín, a leisure administration was therefore set up under the aegis of the camp leaders, the “Freitzeitgestaltung“. It authorized the development on a vast scale of cultural activities, placed under their supervision, poetry or comedy sessions, while musicians were generously exempted from forced labor. The administration also recommended that prisoners correspond with the outside world, in order to calm the anxiety of public opinion, which had questions about the treatment of these imprisoned Jews. Correspondence was monitored, of course.

Surprisingly, the Nazis in Terezin loved jazz!

Soon, the camp was equipped with a lending library that had up to 60,000 volumes. Workshops for theater, painting, writing, poetry, music, classical dance, opera and choral singing flourished. A former student of the Bauhaus in Berlin, who had been taught by Paul Klee and Kandinsky, taught the children to draw. Of all the drawings they produced and which had been lost, 4,000 were miraculously found after the war.

All these Jewish artists were given the opportunity to express themselves in their art, to sing, to organize classical concerts, directed by conductors who had already made their reputation long before they were interned. Among them was the famous Czech conductor Karel Ancerl, who escaped the Holocaust and gave his concerts on a specially installed platform.

But, paradoxically, a jazz group was created, the Ghetto Swingers, whose concerts were filmed and attended by the delighted S.S., while Hitler had formally forbidden the listening and practice of ragtime or swing! Degenerate, of course. But the big difference was that there were no Jews in the audience of these concerts outside the ghetto, where it was of course forbidden to play so-called “degenerate” music.

In the Terezín ghetto, the opera singers even managed to stage operas with sets made by the camp artists. These were real tours de force. The Marriage of Figaro”, Mozart’s “The Magic Flute“, Bizet’s “Carmen“, Johann Strauss’s “The Bat“, Verdi’s “Rigoletto” and “Aida“, Puccini’s “La Tosca“, and the last opera to be staged was Offenbach’s “The Tales of Hoffmann“. It was April 9, 1945, just before the camp closed and the Russians liberated the last Jewish prisoners who had miraculously escaped the horrible “ethnic cleansing.

In a short time, up to 50,000 deportees arrived at this transit camp by rail, while other prisoners left for another destination and were never seen again. It was a sinister traffic of train stations, this station being located at 3 km. on foot of the camp. When this camp housed some 500 Danish deportees, the Danish authorities insisted that the Red Cross come to see how they were treated, in order to dispel the rumors that were circulating about this camp. The Nazis used subterfuge once again

The cruelest of monstrosities

Before the envoy of the International Committee of the Red Cross came to inspect the camp in June 1944, the Nazi camp leaders had evacuated thousands of Jews to Auschwitz in order to mask the appearance of overcrowding at the Terezín camp.

They had also implemented a beautification and flowering plan, opened dummy store windows, built a kindergarten, installed the Danes in freshly painted rooms, put make-up on the sick and overly pale prisoners, and scheduled a performance of the children’s opera, “Brundibar,” by the Czech composer present, Hans Kraza, himself an internee at the camp, for the guests.

In this “Paradiesghetto“, the duplicity of the Nazis was such that Himmler took the opportunity to shoot a propaganda film of the players of this opera, which he entitled “Der Führer schenkt den Juden eine Stadt” (“Hitler gives the Jews the gift of a city”). Everyone was happy to have seen a filmed performance of the opera that castigated the evil Brundibar and emphasized moral values. The Red Cross representative himself was overwhelmed and admitted that he had met healthy, almost happy people in Terezín, in a welcoming setting. However, the film was never shown, but was cut up and distributed in bits and pieces in order to reactivate Nazi propaganda.

But the monstrosity of the Nazi camp leaders soon reached its peak, when the group of children, joyfully excited at having been widely applauded, accompanied by their families, and with the musicians of the orchestra, including the conductor and composer Hans Kraza, as well as the film crew, were deported and gassed in Auschwitz, one after the other, as soon as the filming was over.

Music as the ultimate lifeline

It is therefore easy to understand why music production and creation were so intensely felt in Terezín, because music became a vital necessity for the prisoners who practiced it, a lifeline, however utopian it was. It stimulated their will to refuse what they began to perceive internally: the prospect of a dubious extermination enterprise. The notion of survival animated them and only this lifeline that was music for them, participated in a burst of collective resistance to which musicians, choristers, singers, conductors, adhered. And this common resistance, which Alain Finkielkraut defines in one of his books about the Terezín community, allowed them to survive thanks to this cultural anchoring that prevented the prisoners from sinking into disarray, despair and madness, and where the very personality of each person was shaped and anchored in this collective rejection. It was also a way of escaping anguish, a kind of mental escape but also of spiritual elevation, because art and music carried them towards sublimation.

And we had the proof of it through the song because it conveys words, evocative words that arouse an emotional state in the choristers and the soloists. This choral fusion also had a hymnal dimension that the psychoanalyst Jacques Cheyronnaud describes as “the instantiation of an entity of respect“, the entity of respect being able to be Nation, Fatherland, Israel, Republic, all these terms having value of absolute and being able to be assimilated to Truth, Justice, Freedom, Faith, Victory.

Moreover, the sound process released by the group aroused a quasi-mystical impulse where, as defined by another psychoanalyst Michel Poizat, “the individual identities fade behind the identity of the whole”, thanks to this fusion of the voices and the “hearts of the choirs”. So much so that, for many Jews for whom “this concentration camp system was a terrible misunderstanding” according to the psychoanalyst Bruno Bettelheim, the only way out of this dilemma was to convince themselves that it was a mistake. And it was through this concentration on sung music that some deportees were able to observe a change in their very consideration of Judaism, and that some became painfully aware of their Jewishness and turned once again to their religion, which they had for a moment abandoned.

Verdi’s Requiem: Terezín to transcendence Auschwitz to death

One of the most moving and tragic examples of this transcendence through music was the performance of Giuseppe Verdi’s “Requiem“, although this type of work is not at all part of Jewish culture.

Among the inmates, a Czech pianist and conductor, the Jewish Raphael Schächter, wanted to prove the aberration of Nazi theories by performing this famous work for solo choir and orchestra, a work written by this non-believing musician on evangelical verses of the Catholic religion and performed in Latin by a Jewish community of 150 choristers.

Fascinating! Raphaël Schächter had to spend a lot of time in the barracks and cells in order to gather tenors, sopranos, basses, and solo singers. Schächter hoped to avoid deportation for all these artists. He succeeded in setting up the work in eighteen months, but at the cost of superhuman efforts, by multiplying the rehearsals that took place in the basement, and each time disturbed by impromptu raids during which performers disappeared and never reappeared and had to be replaced by other artists in transit in the camp. A grim situation. Each time, Schächter went back to his “Sisyphean rock“, as it were, and motivated his distraught choristers. But the unshakeable faith of all these performers in freedom and justice took over and could be seen in the emaciated faces of these emaciated and sick men and women, who nevertheless testified to their ability to retain human dignity. And this commitment “ab imo pectore” also impressed the audience, which consisted of the outside public as well as the prisoners of the camp.

At the final performance of the “Requiem”, at which the liquidator Eichmann was present, the 150 singers and the four soloists, accompanied not by an orchestra but by two pianos (a reduced version), succeeded in transforming this mass of the dead into a call to life! The S.S. present remained unmoved. “I will tell the story of how heaven was lost in hell and how hell rose to heaven,” said one of the performers, Joseph Bor, a Jewish resistance fighter who had carried out an attack on a Nazi and escaped the death camp, but whose family, his mother, wife and two children were gassed in Auschwitz. He wrote a book, “The Terezín Requiem”, published in 1963 and republished in 2005, which tells this incredible story and gives his thoughts on that fateful time. For the horrible outcome of this ultimate performance may seem unimaginable, and yet all of them, instrumentalists, singers, conductors, took, one after the other, the direction of the crematoria and mass graves.

The victims of October 1944: cultural genocide

The same was true for Victor Ullmann and all the performers of his opera, who were taken away in the same type of railroad convoys that left on October 16, 1944 and the following days. In these death wagons, artists, musicians, singers, all had the same intellectual approach, fighting for an identical aspiration to truth and justice. Who were they? There was Pavel Haas, whose only unfinished symphony was not completed until 50 years later, the young pianist Gideon Klein, who was an important player in the cultural life of Terezín and who was sent to Auschwitz a few days after completing the composition of his String Trio and Partita for Chamber Orchestra, works that were premiered only 45 years after their rediscovery. Others include Hans Krasa from Prague, the composer of the opera “Brundibar” who, after the last of his 55 performances, was taken to Auschwitz on the night of that fateful October 16, where he died the next day.

For these Jewish artists, both professionals and amateurs, music was the only possible act of resistance against this tragic abomination of history. A whole section of musical creation corresponding to this period of ignominy has been revived over the last few decades, thanks to programmed concerts and recordings of these works, which were belatedly rehabilitated and conceived not only in Terezín but also in a few other death camps where music was made. In any case, it is a generation of Jewish performers, soloists and composers, sacrificed on the altar of barbarism, who were thus victims of what can be called a cultural genocide.

Georges Masson (in Memoriam)

Journalist, author and music critic, ardent supporter of WUKALI