Season II

Part 2

From the Italian Renaissance

It is difficult to imagine today what the domination of Paris over modern art was before World War II. In this regard, New York was then just an unimportant province, far from the relevant circuits.

The fall of Paris, the “city of light”, in the hands of the Nazis, was seen by American intellectuals as the symbol of the end of civilization, as the end of democracy and freedom symbolized by the artists of Montparnasse, and like the victory of barbarism.

In an editorial in the “Shreveport Times” in June 1940, it was said that “it was freedom that made Paris great. Men and women were free to use their talent to the full, without constraint … no narrow-minded politician could tell them what to say or think … this freedom was not reserved for the elite alone intellectual … a man in the street or a woman in his kitchen could also benefit ”. And the “Daily Oklahoma” added that “nothing like it, against democracy and the Christian way of life, nothing more powerful, more ruthless, more insecupulous, had been seen in the past since Genghis Khan and Attila ”. Harry Truman added that “the role of this great Republic (the United States) was therefore to save civilization“.

It appeared, therefore, that the traditional role of Europe was now devolved to the United States; and American politicians readily accepted the idea that art was going to play a central role in this new America, and that what the West held most precious: its culture had to be saved.

As Paris fell into the hands of the Nazis, the American government, without wasting time, organized, from November 25 to December 1, 1940, a “Buy American Art Week“, so that American artists could contribute to the victory “of life against death ”. Life magazine reproduced works, the government effort now to educate the public in art. An effort that was considerable: 32,000 artists participated in this “Buy American Art Week“, 1,600 exhibitions were organized across the United States.

Thus Georges Biddle, an American painter who produced, among other things, a large mural for the Robert F. Kennedy building, the building of the Department of Justice in Washington, and who was a childhood friend of President Roosevelt, played an important role in the “Works Progress Administration” (“WPA”) program, the purpose of which was to employ American artists to enable them to make a living from their art. Although these programs were not an immediate success, Biddle could compare the boiling that was beginning to occur in the United States to the “Italian renaissance“.

From Byzantium to New York

To all the misfortunes that Nazism caused in Europe, one more should be added: the exile of tens of thousands of the best intellectuals and artists of the time to New York. This influx of talent from Europe greatly impressed Americans, and some commentators compared this exile either to a new century of Pericles in the making, or to that of the artists who took refuge in Italy after the Turkish capture of Constantinople in 1453. New York became Byzantium !!

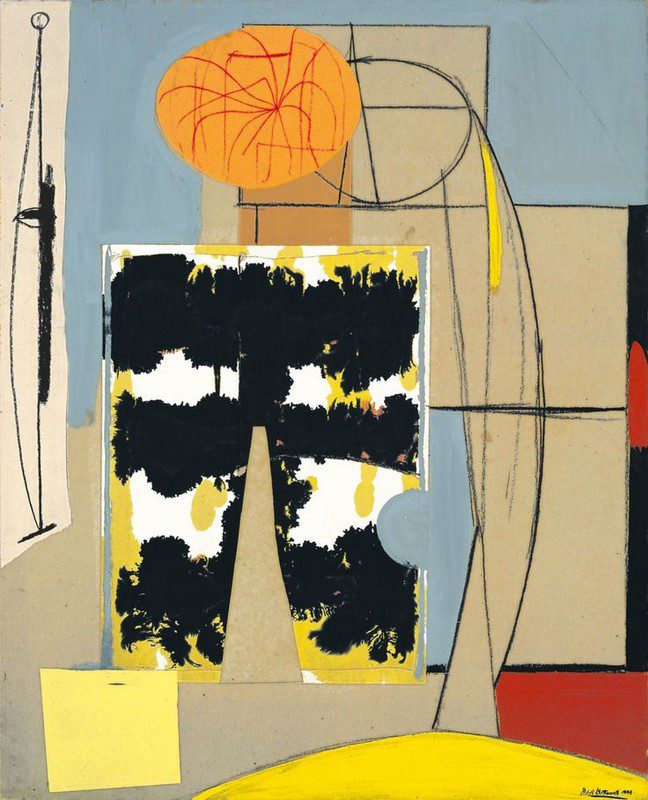

University of California, Berkeley Art museum et Pacific Film archive, given by Hans Hofmann, 1965. 17,©Succession Hans Hofmann/ARS, New York, NY

But Americans soon realized the opportunity that these massive arrivals would represent, not to imitate European art, but on the contrary to create an authentically American art, an art hitherto unknown and even despised. “You could say that the center of Western culture is no longer in Europe. He’s in America. It is we who are the arbiters of its future and it is we who bear this immense responsibility. The future of art is in America ”, wrote John Pearson Bishop in 1941, poet and friend of F. Scott Fitzgerald (who also serves as a model for one of Fitzgerald’s characters in“ The Back of Heaven “).

Samuel Koots, who owned a gallery at the corner of 57th Street and Madison, and who was one of the early advocates of the American pictorial avant-garde, in turn wrote in a letter to the New York Times that “Under the present circumstances, it is likely that the future of painting lies in America … now is the time to innovate … you have complained for years that Parisian merchants are robbing the American market ..” all you have to do now, boys and girls, is try a new approach ”.

It was a new approach indeed! For Koots was a businessman who knew the secrets of marketing and immediately saw the possibility of a new and lucrative market.

It was then that the New York Times described this letter as a “bomb”, a bomb which rejected the ideas of the Popular Front and denounced painting as it was practiced until then in the United States; it was essential to find something new. Yet such art did exist, except that it was not recognized by museums. Artists then created a group, the “Bomshell Group“, but it was not especially successful.

Crédits: Leemage-AFP

On the other hand, Koots, after the publication of his letter, received an invitation from the Macy’s department store asking him to set up an exhibition, which was one of the first attempts to open a new market, a mass market.

In 1942, Peggy Guggenheim, meanwhile, opened a new gallery called The Art of This Century Gallery. Peggy Guggenheim’s taste was certainly not very certain, but she surrounded herself with experts, including Marcel Duchamp (whom André Breton called “the most intelligent man of the century“), the same who, in 1917, had been the creator of the sculpture “Fountain“, which consisted quite simply of an overturned urinal (one finds replicas of it in various museums, of which the Tate). But if Peggy Guggenheim did not have such a wonderful taste, she was a formidable businesswoman; she too had felt the wind …

It was then that the museums joined in, each defending its own square: The Museum Of Modern Art (MoMA) represented the nouveau riche, the young, the liberals; while the Metropolitan Museum (the Met), whose “trustees” represented the old American aristocracy, leaned towards academism, prudence, restraint. The battle for the cultural domination of New York was on.

Business to business

It was a success. Between 1942 and 1943, the number of visitors to the Met increased by 15%, reaching nearly 1.4 million visitors in 1943. Museums became a propaganda tool, the Met, for example, supporting the “Artists for Victory” movement. », And exhibitions on military themes were organized there; as for MoMA, it was not to be outdone, organizing an exhibition in 1942 whose name was “Road to Victory“, which showed the military might of the United States. Thus was instilled in the public the idea that the defense of culture had become crucial in the defense of civilization.

Businessmen and publicity followed. At a time when French art was no longer exported, and inflation was inexorably increasing, an “art boom” was emerging. Suddenly the United States discovered an insatiable appetite for art. The number of galleries in New York rose from 40 to 150 at the end of the war, sales rose from 2.5 million in 1939 to 4 million dollars in 1942, and so on. We bought paints to protect ourselves from inflation.

Art sellers invented new methods of selling, you could even buy from “artists’ co-operatives”, or outright by mail order. The profile of clients changed, art became a commodity and galleries became supermarkets; and since the new buyers were patriots, they wanted to buy American art.

“New buyers almost exclusively acquire American works. American painters are cheaper, there are more of them, they are easily found which are of good quality. It is a patriotic act to help American artists, “wrote Aline Louchheim in” Who buys what in the picture boom “, Art News 1944.

Macy’s, not to be outdone, placed an advertisement in the New York Times in 1943, but this time to sell European art: “Macy’s is selling authentic paintings by Rembrandt, Rubens, etc. . $ 130,000 of paintings sold at the tightest price; payment of 1/3 when ordering, the rest spread over several months “

Home decor magazines rushed into the breach, and Life magazine offered its advice, becoming the arbiter of elegance.

In 1944, Harper’s Bazar presented a collection of clothes with a painting by Fernand Léger and another by Piet Mondrian in the background. Harper’s Bazaar did Pollock credit as well, and so art became an object of desire, the ultimate stage in consumer society.

Obviously, this was not to the taste of the super-rich who, to distinguish themselves, began to buy abstract expressionists.

Others complained as well, but for other reasons: in 1945, Henry Miller vituperated against Philistine America, regretting the artists of Montparnasse who wore a beret:

“I could have escaped this American war. I could have become a good citizen and made some money…. There is no real life in America for an artist -except a living dead … A painter who wants to survive has to paint stupid portraits of even stupider people, or else sell his services to the kings of advertising. who I think have done more to ruin art than anything else I know ”. (“The air-conditioned nightmare”, Henry Miller, 1945).

We had entered another world … that of conquering America.

Next article: The apotheosis of Pollock. on line Thursday March, 4th

(*) Bibliography :«Comment New-York vola l’idée d’art moderne», Serge Guilbert, Pluriel 1982

Publishing calendar

À l’aube du XXIéme siècle

by Jacques Trauman

Saison 1

La « French Theory » et les campus américains

Episode 1. Erudition et savoir faire. Jeudi 25 février

Episode 2. Citer en détournant. Vendredi 26 février

Episode 3. Le softpower américain. Samedi 27 février

Saison 2

Comment New-York vola l’idée d’art moderne

Episode 1. Du Komintern à la bannière étoilée. Mardi 2 mars

Episode 2. En route pour la domination mondiale. Mercredi 3 mars

Episode 3. L’apothéose de Pollock. Jeudi 4 mars

Episode 4. La guerre froide de l’art. Vendredi 5 mars

Saison 3

Aux sources du softpower américain

Episode 1. Guerre froide et « Kulturkampf ». Mardi 9 mars

Episode 2. Quand les WASP s’en mêlent. Mercredi 10 mars

Episode 3. Ce n’était pas gagné d’avance. Jeudi 11 mars

Episode 4. Un cordon ombilical en or. Vendredi 12 mars

Illustration de l’entête: Edward Hopper, Nighthawks, 1942. The Art Institute of Chicago, IL, USA, Friends of American Art Collection